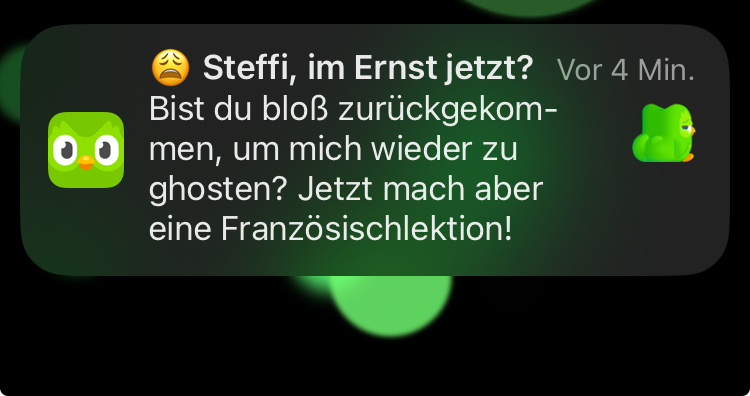

The moment that inspired this article

For months, I successfully ignored Duolingo. Learning French again? Nice idea, but somehow lost between work, teaching assignments, and psychology studies. Yesterday: Downloaded an app update, opened it briefly, closed it again. So... yeah: did nothing.

Dann hab ich später auf mein Handy geschaut und da ist sie, diese Notification: “Did you just come back to ghost me again? Now do a French lesson!” Ich musste echt kurz lachen. Dann kam die UX Designerin in mir durch: Why does this work so well and "catch" my attention?

From my own experience: What other apps say

To understand why Duolingo's approach is special, let's look at how other apps communicate with inactive users:

- Garmin: Status "unproductive" after a 15 km run on Sunday at 7 am (Um... thanks?)

- To-Do-Apps: "12 overdue tasks are waiting for you" (I know. That's why I'm not opening the app, haha.)

- Social Media: "You're missing what your friends are posting right now!" (FOMO as a business model.)

- Meditation-Apps: "Your 30-day streak is lost 😔" (Note the irony that a meditation app creates stress...)

So, in summary, most apps use a combination of guilt, artificial urgency, loss aversion (= you're "losing" something), and social pressure. Duolingo does something different.

The Anatomy of Good UX Writing: What Duolingo Gets Right

1. Self-irony instead of guilt-tripping

„Did you just come back to ghost me again?”

The app says what I'm thinking myself – before I can formulate it. It knows my behaviour (downloading an update, opening it to... well... do nothing) and comments on it with a wink. No accusation, but rather "I see through you, and that's okay."

Why this works: People react defensively to accusations, but openly to humour. The self-ironic tone signals: "We don't take ourselves too seriously – and we don't judge your behaviour either."

But wait – isn't this also guilt-tripping?

At first glance, you might think: The "ghosting" accusation, that's also guilt induction! But there's a crucial psychological nuance here.

Classic guilt induction (à la Garmin)

- Focus is on failure: "You are unproductive"

- Identity level is attacked (even if implicitly): "You are inactive/lazy/unmotivated" (addresses the person instead of the behaviour)

- Focus on past and loss aversion: Emphasis is on what you've already lost.

- Comparison with others: "Others have already achieved this and that..."

The emotional effect is usually shame and resignation, so rather negative. Duolingo's approach doesn't judge you:

- Keeps focus on your behaviour: "You're ghosting" (not "You are a ghoster")

- Stays on the situational level: Describes what you do, not who you are (Gollwitzer, 1993, 2006) (vgl. Gollwitzer, 1993,2006)

- Is present-oriented: "Now do..." (call to action)

- No comparison with others: Just you and the owl

It does have an emotional effect, but a positive one: You feel caught, but you have to smile. That leaves a good feeling rather than a bad one.

The crucial difference: Duolingo names the behaviour playfully, without judging the person. That's a huge psychological difference. I can change behaviour, but not my identity. Additionally, the owl presents itself as the "victim" ("...ghost me"), which humorously turns the tables. I don't feel bad about myself, but smile about the situation. This doesn't trigger defensiveness, but opens me up to the call to action.

2. Anthropomorphisation* with personality

The Duolingo owl isn't a neutral learning AI. It's a personality – perhaps sometimes slightly passive-aggressive, always persistent, but ultimately – and this is the thing: on your side. It reminds us of people we know: the friend who asks, "When will we finally see each other again?" or the trainer who says, "Great that you're here – now actually do something!"

That differs from other apps: The owl is consistent in its personality. Not sometimes sweet, sometimes strict, sometimes desperate. It has a recognisable character, and that's exactly what creates a relationship.

*Anthropomorphisation = psychological attribution of human characteristics to a non-living object

3. Honesty over manipulation

„Now do a French lesson!“

No false urgency ("Only 2 more hours!"), no fake scarcity ("Last day!"), no emotional blackmail. Instead: a direct request. Almost cheeky, but very honest.

Psychologically clever: This almost cheeky directness feels refreshing in a world full of manipulative notifications. We're so used to deceptive patterns that honesty is surprising and positive.

4. Timing and context

The notification didn't come randomly. It came exactly after I opened the app and closed it again – without completing a French lesson. That's precise behavioural tracking, but in service of a meaningful intervention. (Fogg, 2003)

The context makes a difference. With a shopping app, the same timing would be creepy ("You looked but didn't buy?"). With a learning tool, it's legitimate. Read more about context in Part 2 (coming soon!).

What we've learned so far

Duolingo's notification works because it:

- comments on behaviour instead of judging identity

- Has a consistent personality that creates a relationship

- Is honest instead of manipulative

- Understands context and is perfectly timed

But here comes the crucial question: Why does this tone work so well with Duolingo – and would be toxic with Instagram or TikTok? Where is the ethical boundary between charming motivation and manipulative retention?

Part 2 of this article will cover:

- Why the same tonality motivates with Duolingo – and manipulates with Instagram

- A 3-question framework for ethical engagement design

- 4 practical steps to the right tone for your product

Follow us on LinkedIn (www.linkedin.com/company/birdux-studio) or Bluesky (bsky.app/birdux) so you don't miss Part 2.

Sources

- Fogg, B. J. (2003). Persuasive technology: using computers to change what we think and do. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). „Implementation Intentions: Strong Effects of Simple Plans.“ American Psychologist.

- Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). „Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes.“ Advances in Experimental Social Psychology.

- Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). „Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes.“ Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Rationality in action: Contemporary approaches (pp. 140–170). Cambridge University Press. (Reprinted from „Econometrica“ 47 (1979), 263-91)

Article Image Character from https://duolingopress.lingoapp.com/